By Sara W. Koblitz —

Further talks of the Skinny Label’s demise may be premature, as demonstrated by a new decision from the District Court for the District of Columbia upholding FDA’s interpretation of the “same labeling” provisions of the Hatch-Waxman Amendments. That is not to say that concerns about the induced infringement theory at issue in GSK v. Teva and Amarin v. Hikma are no longer relevant—they very much are—but the newest theory posed in Novartis v. FDA, arguing that labeling modifications are impermissible, has been squarely rejected. There, as we explained back in July, Novartis argued that FDA’s approval of a generic ENTRESTO with indication information modified rather than simply omitted “represents a sharp departure from FDA’s statutory and regulatory mandate to require that a generic drug be the ‘same’ as its reference listed drug.” Novartis additionally alleged that FDA unlawfully permitted the carve-out of critical safety information of a modified dosing regimen and unlawfully approved an active ingredient that was not the “same” as the Reference Listed Drug (“RLD”). In a redacted opinion published October 15, 2024, the DDC granted FDA and intervenor MSN’s Motion for Summary Judgment, rejecting all of Novartis’s allegations and holding that FDA’s approval of MSN’s product did not violate the Administrative Procedure Act or the FDC Act.

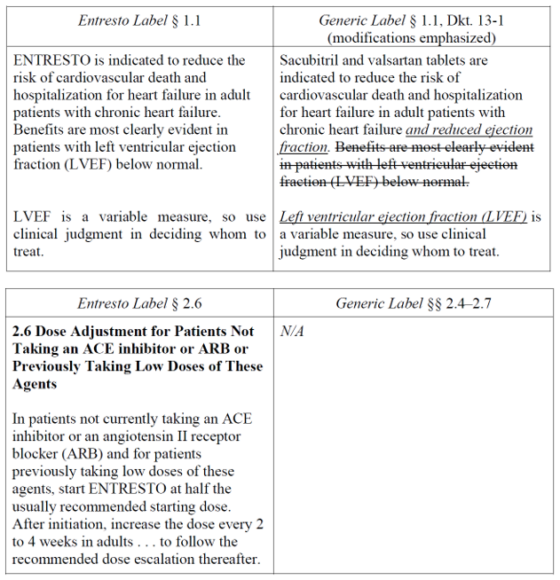

In brief, ENTRESTO was once approved “to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalization for heart failure in patients with chronic heart failure (NYHA Class II-IV) and reduced ejection fraction” but its labeling was subsequently amended to reflect that the product is approved to treat all patients with chronic heart failure, and to add a new dosing regimen for specific patients. While denying a Citizen Petition from Novartis asking FDA to refuse to approve any ANDA that omits the new dosing regimen or changes the indication, FDA approved MSN’s ANDA on July 24, 2024. FDA, in its Citizen Petition Denial, stated that it retains the authority to approve generic labeling that modifies an approved indication and that it could lawfully approve generic labeling that omits the modified dosing regimen in ENTRESTO’s labeling. To that end, FDA approved the MSN ANDA without the modified dosing regimen and with the indication “to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalization for heart failure in adult patients with chronic heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. Benefits are most clearly evident in patients with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) below normal. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is a variable measure, so use clinical judgment in deciding whom to treat.” The labels differed as such: (here)

Novartis sued FDA arguing that the FDC Act requires generic labeling to match the current labeling for the reference listed drug—not the discontinued labeling—and that the new MSN labeling violates the statutory requirement that the indications for a generic be “the same” as its RLD. Novartis noted that FDA’s regulations permit only the “omission of an indication”—not the modification of the product’s currently approved indication—and asserted that FDA failed to explain “how a full cloth rewriting of the reference drug’s labeling is consistent with the rest of the ENTRESTO labeling” and that the modified labeling, especially considering the omission of the modified dosing regimen, “renders [the MSN product] both less safe and less effective.” Novartis also argued that FDA’s approval of the active ingredients in the MSN product violate active ingredient sameness requirements, as ENTRESTO is a contiguous valsartan-sacubitril-sodium complex while the generic is a physical mixture of individual sodium salts.

Noting the change in review standard from Chevron deference to Loper Bright, the DDC nonetheless found that “MSN’s generic drug is consistent with FDA regulatory and statutory requirements that require a generic drug to have the same label and active ingredients as the reference drug.” Citing to “[b]inding Circuit law” in Bristol-Myers Squibb v. Shalala, the Court explained that the law “permits changes to generic’s label to account for patient-protected indications.” The Court noted that the D.C. Circuit interpreted the relevant statutory provisions itself—it did not defer to FDA’s interpretation—and thus Bristol-Myers remains good law even in light of Loper Bright. Additionally, the Court found no support in the record for Novartis’s claim that FDA reverted back to original labeling rather than comparing the MSN labeling to the most recently approved ENTRESTO labeling. The Court further “agree[d] with FDA that an ‘omission’ under the regulation must turn on the ‘substance of the information that is omitted—not whether that substantive omission is accomplished by adding words or deleting them.’” Thus, Novartis’s position, “that a generic drug label may only omit patented uses by deleting words rather than adding them—puts form over substance.” Adding words, said the Court, is consistent with FDA precedent.

The Court also found that FDA did not act arbitrarily by excluding the patent-protected dosing regimen from MSN’s labeling. The Court deferred to FDA’s determinations about the categorization of chronic heart failure patients and about the carve-out of the dosing regimen, as both issues are in FDA’s “area of technical expertise.” Novartis failed to demonstrate that the modified labeling affects the drug’s safety and efficacy and FDA thoroughly explained its rationale in its Citizen Petition response. Finally, the Court reviewed FDA’s scientific determinations about active ingredient sameness for reasonableness and consistency with the evidence in the record and deferred to FDA’s determination that the two products contain the same active ingredients. The Court stated that “FDA’s determination on chemical identity sameness reflects its reasoned ‘scientific analysis,’ which deserves ‘a high level of deference,’” as it is “pure scientific judgment.” FDA’s determination that the products contain the same active ingredients was “rational, carefully explained, and consistent with the record evidence;” thus, the Court will not “unduly second-guess” FDA’s judgment.

By leaving intact Bristol-Myers Squibb, notwithstanding the argument that Loper Bright nullifies it, the Court preserved an important avenue for generic drug manufacturers. The skinny label—whether utilizing omission or labeling modification—can continue to exist, allowing generic manufacturers to come to market earlier for non-protected uses of RLDs. We note, however, that this is unlikely to be the last affront to the skinny-label, which clearly remains a target for RLD sponsors.